How Much Protein Do You Need?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

In 2016 the New York Times ran an article with the title, “Can You Get Too Much Protein?” The article asserted that most Americans were getting too much protein in their diet and that protein supplements were useless and perhaps dangerous.

In 2016 the New York Times ran an article with the title, “Can You Get Too Much Protein?” The article asserted that most Americans were getting too much protein in their diet and that protein supplements were useless and perhaps dangerous.

At the time I wrote a “Health Tips From the Professor” article summarizing recent research showing that many people needed more than the RDA for protein and that those people were often consuming too little, rather than too much, protein.

In the 9 years since then the evidence that many Americans may not be getting enough protein has only gotten stronger.

- The standard for protein intake used to be a “one size fits all” recommendation of 46g gm/day for women and 56 gm/day for men with slight increases recommended for pregnant and lactating women. Today we know:

-

- That standard was based on outdated methodology from the 1930’s. Recent studies suggest protein intake should be at least 50% higher.

-

- That standard was based on studies with healthy, sedentary adults (the adult “couch potato” crowd). Protein requirements are significantly higher for anyone who doesn’t fit that description.

- We used to think in terms of total daily protein intake. Today we know that:

-

- Protein intake should be divided equally between the 3 primary meals.

-

- Protein quality is important. Protein requirements should be increased if low-quality proteins are consumed.

- We used to worry that high protein intake might damage your kidneys. Today we know that:

-

- Protein intake does not cause kidney disease. It is not a concern as long as hydration is adequate and excess alcohol is avoided.

-

- Protein intake is only a concern if someone has kidney disease.

Protein – Your Longevity Nutrient

If you want to delve into the latest protein research and what it means for you, I highly recommend the book, “Forever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy For Aging Well” by Dr. Gabrielle Lyon.

If you want to delve into the latest protein research and what it means for you, I highly recommend the book, “Forever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy For Aging Well” by Dr. Gabrielle Lyon.

Her book is focused on helping each of us create adequate healthy muscle mass. She says, “Adequate muscle mass is essential for health and longevity. And muscle is the only organ over which we have voluntary and complete control.”

Of course, adequate muscle mass requires both exercise and adequate protein. Dr. Lyon covers both in her book, but exercise is not my expertise, so I will only cover adequate protein intake in this “Health Tips From the Professor” article.

In her book, Dr. Lyons details recent research on the amount of protein needed to optimize muscle mass. Dr. Lyon was the one who alerted me to the fact that the current protein RDA is based on outdated methodology from the 1930’s and that actual protein needs are much higher.

Dr. Lyon concludes that most Americans are not consuming enough protein to optimize their muscle mass and that adequate protein intake is essential for longevity, metabolic function, and quality of life. Specifically, she says that optimal muscle mass:

- Improves strength and mobility.

- Improves blood sugar control.

- Decreases blood triglyceride levels.

- Strengthens the immune system.

- Improves bone mineral density and strength.

- Reduces all-cause mortality (risk of dying) and morbidity (risk of disease).

I will use the latest science on protein needs described in her book and in recently published clinical studies to answer the important question, “How much protein do you need?” But first I want to help you understand the dynamics of protein metabolism.

The Dynamics Of Protein Metabolism

Most people associate muscle mass with strength and endurance. Many understand the important role muscle mass plays in burning off excess calories and keeping us slim. But few people understand the important role that muscle protein plays in our everyday energy metabolism.

Most people associate muscle mass with strength and endurance. Many understand the important role muscle mass plays in burning off excess calories and keeping us slim. But few people understand the important role that muscle protein plays in our everyday energy metabolism.

Whenever we eat a meal containing protein, we store some of the protein we eat as increased muscle mass, especially when protein intake is coupled with exercise. But muscle protein plays other very important functions. It is a precious resource.

The synthesis of new muscle in the fed state is driven by:

- Insulin, which is released into the blood stream whenever we eat a meal.

- Exercise because it makes muscle more sensitive to the effects of insulin.

- The amino acid leucine, which is most abundant in high quality protein sources.

In the fed state most of our energy is derived from blood glucose. This is primarily controlled by insulin. As blood glucose levels fall, we move to the fasting state and start to call on our stored energy sources to keep our body functioning. This process is primarily controlled by a hormone called glucagon.

- In the fasting state most tissues easily switch to using fat as their main energy source, but…

-

- Red blood cells and a few other tissues in the body are totally dependent on glucose as an energy source.

-

- Our brain is normally dependent on glucose as an energy source, and our brains use a lot of energy. [Note: Our brain can switch to ketones as an energy source with prolonged starvation or prolonged carbohydrate restriction, but that’s another story for another day.]

- Because our brain and other tissues need glucose in the fasting state, it is important to maintain a constant blood glucose level between meals.

-

- Initially, blood glucose levels are maintained by calling on carbohydrate reserves in the liver.

-

- But because those reserves are limited, our body starts to break down muscle protein and convert it to glucose as well – even in the normal dinner/sleep/breakfast cycle.

Simply put, in addition to its other important roles in the body, muscle protein is also an energy store. You can think of it like a bank.

When we eat, we make a deposit to that energy store. Between meals we make a withdrawal from that energy store. When we are young the system works perfectly. Unless we fast for prolonged periods of time, we are always adding enough muscle protein in the fed state to balance out the withdrawals between meals.

But there are many physiological situations where protein metabolism becomes unbalanced, either because protein breakdown is accelerated or because protein synthesis is diminished. In each of those situations, our protein needs are increased.

I will describe each of these situations and how they affect our protein needs in the section below.

How Much Protein Do You Need?

The Coach Potato Group: If this is you, I won’t be judgmental. But I highly recommend you read Dr. Lyon’s book. It may just inspire you to increase your fitness level and your protein intake.

The Coach Potato Group: If this is you, I won’t be judgmental. But I highly recommend you read Dr. Lyon’s book. It may just inspire you to increase your fitness level and your protein intake.

As I said before the standard RDA recommendation for the coach potato group is 46 gm/day for women and 56 gm/day for men. That’s based on 0.36 grams of protein per pound of body weight and assumes that women weigh around 127 pounds and men weigh around 155 pounds.

There are two major problems with the standard protein RDAs:

1) The protein RDA should not be a “one-size-fits-all” recommendation. The standard used to calculate the RDA is based on weight. If you are a woman weighing 127 pounds or a man weighing 155 pounds, you are to be congratulated. But in today’s world the average woman weighs 170 pounds, and the average man weighs 201 pounds.

- That means the average protein requirement should be 61 gm/day for women and 72 gm/day for men.

- And that’s just the average. Your protein requirement is based on your weight.

2) As I mentioned earlier, the 0.36 gm/pound standard is based on outdated methodology from the 1930’s. Based on current technology, Dr. Lyon says the standard should be closer to 0.54 gm/pound.

- If you use that standard and use the current average weight for men and women, the average protein requirement for the couch potato group is closer to 91.5 gm/day for women and 108 gm/day for men.

- And since protein intake should be divided equally between meals, that amounts to 30 gm/meal for women and 36 gm/meal for men. If you weigh significantly more or less than the average American, you should adjust your intake accordingly.

The Over 50 Group: When we are young muscle protein deposits in the fed state and muscle protein withdrawals during the fasting state are in balance. And if we add exercise and increase our protein intake, it’s pretty easy to increase our muscle mass.

The Over 50 Group: When we are young muscle protein deposits in the fed state and muscle protein withdrawals during the fasting state are in balance. And if we add exercise and increase our protein intake, it’s pretty easy to increase our muscle mass.

But once we reach our Golden Years things start to change. Muscle protein synthesis becomes less efficient. We need to increase the intensity of our workouts and increase our protein intake just to maintain our muscle mass.

If we fail to do that, we gradually lose muscle mass as we age, a process referred to as sarcopenia. Between 50 and 60 we lose 5-8% of our muscle mass, and the rate that we lose muscle accelerates with each subsequent decade. And that loss of muscle mass has severe consequences. For example:

- It interferes with daily activities like playing with our grandchildren and engaging in activities we love.

- It decreases our metabolic rate which increases our risk of obesity and obesity-related diseases.

- It increases our risk of falls.

In short, our quality of life is diminished, and we become unhealthy and frail.

Dr. Lyon describes the training program needed to prevent sarcopenia as we age in her book Forever Strong. But we also need more protein.

On average older adults need around 35 – 45 gm of protein per meal to prevent sarcopenia. There are not enough published studies for me to provide more specific recommendations. But here are some guidelines:

- If you are at ideal weight and in your 50’s or 60’s, you can probably do well at the lower end of the range.

- If you are overweight or in your 70’s or 80’s, you should probably aim for the upper end of the range.

- I recommend getting a body composition test on an annual basis and adjusting your exercise and protein intake based on your change in muscle mass. My doctor has a simple device for measuring my body composition as part of my annual physical. If your doctor doesn’t have a device like that, find out who does in your community.

The Weight Loss Group: If you are actively trying to lose excess weight, I congratulate you. But the sad fact is that up to 35% of weight loss on most diets comes from muscle, not fat.

The Weight Loss Group: If you are actively trying to lose excess weight, I congratulate you. But the sad fact is that up to 35% of weight loss on most diets comes from muscle, not fat.

That’s because your body interprets caloric restriction as starvation and increases the rate of protein breakdown.

But you can prevent that by adding resistance training to your diet plan and increasing your protein intake. By increasing your protein intake from 15% of calories (which is what most Americans get) to 30% of calories, you can rebalance muscle metabolism by increasing muscle protein synthesis. When you do this, you can reduce muscle loss to less than 10% of weight loss.

You may be wondering, “Why set the recommendation as a percentage of calories rather than gm/pound or gm/meal”. The answer is simple. Your caloric intake changes significantly you are on a diet, so expressing protein as a percentage of calories makes more sense.

For example, 30% of calories on a 1,000-calorie diet translates into 25-30 gm/meal. You might look at that recommendation and say, “That’s less than you recommended for the couch potato who is not trying to lose weight.” My answer would be, “Yes, but the couch potato is eating 2-3-times more calories.

So, the recommendation that’s easiest to understand if you are trying to lose weight is to aim for 25-30 gm of protein/meal/1,000 calories per day.

- Adjust your protein intake per meal based on the daily calories allowed on your diet.

- And if you are on a diet that restricts the kinds of food that you can eat or the amount of time you can eat, track your actual caloric intake for a few days. The “hidden secret” behind those diets is that most people eat fewer calories because of the restrictions.

Final thought: The latest data suggest that GLP-1 drugs accelerate the muscle loss associated with dieting. This is a significant concern, especially for people over 50. Some experts are recommending as much as 35-50 gm of protein/meal if you are using a GLP-1 drug to aid your weight loss.

The Fitness Group: The question I get most often from the fitness group is, “How much protein do I need after my workout to maximize recovery and muscle gain?” This has been well researched, and the answer is age dependent.

The Fitness Group: The question I get most often from the fitness group is, “How much protein do I need after my workout to maximize recovery and muscle gain?” This has been well researched, and the answer is age dependent.

- If you are in your 30’s, most experts recommend 15-20 grams of protein after your workout.

- If you are in your 60s, most experts recommend 30-35 grams of protein after your workout.

- While precise recommendations are not available for every age, you can extrapolate from these numbers.

Does Protein Quality Matter?

I’m often asked whether all proteins are equally effective at building muscle mass or does protein quality matter? The answer is, “Yes. Protein quality matters, but not in the way that we have thought about it in the past.”

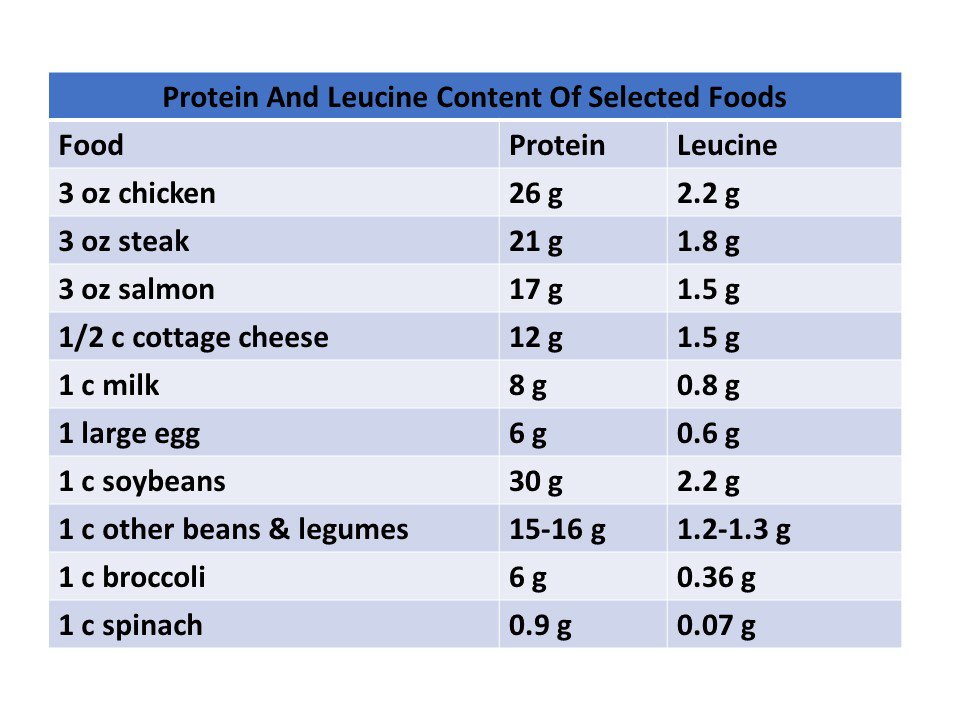

We used to think that protein quality was measured by the balance of all the essential amino acids. While balance is important, the increase in muscle mass is driven primarily by the amino acid leucine. That’s because leucine is the only amino acid that directly stimulates muscle protein synthesis.

Simply put, proteins that are high in leucine are used more efficiently by our bodies to increase muscle mass. In fact, Dr. Lyon measures protein quality solely based on its leucine content.

Many studies have looked at the optimal amount of leucine content in protein. The numbers vary somewhat from study to study, but they average around 1 gram of leucine for every 10 grams of protein.

If you look at the leucine contents of various proteins, it is clear that a 1:10 ratio is primarily found in animal proteins. Soybeans are the only vegetable protein source that comes close. However, there are many health reasons for consuming a primarily plant-based diet. Dr. Lyon doesn’t tell her patients to avoid plant proteins. But if they are consuming primarily plant proteins, she recommends that they increase their protein intake by 35-45%, so they will be getting enough leucine to maximize muscle protein synthesis.

However, there are many health reasons for consuming a primarily plant-based diet. Dr. Lyon doesn’t tell her patients to avoid plant proteins. But if they are consuming primarily plant proteins, she recommends that they increase their protein intake by 35-45%, so they will be getting enough leucine to maximize muscle protein synthesis.

What Role Do Protein Supplements Play?

Remember that New York Times article that said protein supplements were useless and perhaps dangerous? That’s outdated advice. In fact, you should view protein supplements as essential for reaching your protein goals.

Remember that New York Times article that said protein supplements were useless and perhaps dangerous? That’s outdated advice. In fact, you should view protein supplements as essential for reaching your protein goals.

That’s because our protein intake needs to be divided equally between our 3 major meals, but that’s not how we eat. Most of us have no trouble getting 30-40 grams of protein at dinner, but…

- We only get around 15 grams of protein at breakfast, and…

- 15-20 grams of protein at lunch.

But that’s assuming we eat a typical breakfast or lunch. If we eat…

- An unhealthy breakfast of croissants and coffee or a healthy breakfast of cornflakes, skim milk, and fruit slices, we only get around 6 grams of protein.

- A healthy green salad for lunch, we may get as little as 2 grams of protein.

A recent study has shown that adding a protein supplement to your low protein meals can help you increase your muscle mass in as little as 24 weeks.

What Does This Mean For You?

Protein is your longevity nutrient. My advice is:

Protein is your longevity nutrient. My advice is:

- Use the information in this article to set your protein goals (Talk with your doctor first if you have any health issues that may limit your protein intake).

- Use a simple protein tracker to identify your low-protein meals.

- Add additional protein foods or supplements to your low-protein meals to bring your protein up to recommended levels.

- Focus on high-leucine protein foods and supplements. (If you eat more plant protein than animal protein, as I do, increase your recommended protein intake by 35-45% to make sure you are getting the leucine you need to maximize your muscle mass.)

As for what kind of protein supplement, I recommend a plant protein supplement with added leucine.

The Bottom Line

In her book, “Forever Strong”, Dr. Gabrielle Lyon says, “Adequate muscle mass is essential for health and longevity. And muscle is the only organ over which we have voluntary and complete control.” She goes on to state that the current RDAs for protein intake are outdated. And if we look at protein needs based on the latest research, most Americans aren’t getting enough protein in their diet to achieve adequate muscle mass.

In this article, I summarize her findings. And based on the latest research, I provide protein intake recommendations for:

- Adult couch potatoes.

- Fitness enthusiasts.

- People over 50.

- People who are trying to lose weight.

I also discuss protein quality and protein supplements.

For more information on these topics and what they mean for you, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

_____________________________________________________________________________

My posts and “Health Tips From the Professor” articles carefully avoid claims about any brand of supplement or manufacturer of supplements. However, I am often asked by representatives of supplement companies if they can share them with their customers.

My answer is, “Yes, as long as you share only the article without any additions or alterations. In particular, you should avoid adding any mention of your company or your company’s products. If you were to do that, you could be making what the FTC and FDA consider a “misleading health claim” that could result in legal action against you and the company you represent.

For more detail about FTC regulations for health claims, see this link.

https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/health-products-compliance-guidance

______________________________________________________________________

About The Author

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years.

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years.

Dr. Chaney won numerous teaching awards at UNC, including the Academy of Educators “Excellence in Teaching Lifetime Achievement Award”.

Dr Chaney also ran an active cancer research program at UNC and published over 100 scientific articles and reviews in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition, he authored two chapters on nutrition in one of the leading biochemistry text books for medical students.

Since retiring from the University of North Carolina, he has been writing a weekly health blog called “Health Tips From the Professor”. He has also written two best-selling books, “Slaying the Food Myths” and “Slaying the Supplement Myths”. And most recently he has created an online lifestyle change course, “Create Your Personal Health Zone”. For more information visit https://chaneyhealth.com.

For the past 53 years Dr. Chaney and his wife Suzanne have been helping people improve their health holistically through a combination of good diet, exercise, weight control and appropriate supplementation.