Why Is Nutrition So Confusing?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

Sometimes the professor likes to introduce you to the frontiers of nutrition. Epigenetics is such a frontier. In recent years, the hype has centered on DNA sequencing. It seems like everyone is offering to sequence your genome and tell you what kind of diet is best for you, what foods to eat, and what supplements to take. But can DNA sequencing fulfill those promises?

Sometimes the professor likes to introduce you to the frontiers of nutrition. Epigenetics is such a frontier. In recent years, the hype has centered on DNA sequencing. It seems like everyone is offering to sequence your genome and tell you what kind of diet is best for you, what foods to eat, and what supplements to take. But can DNA sequencing fulfill those promises?

The problem is that DNA sequencing only tells you what genes you have. It doesn’t tell you whether those genes are active. Simply put, it doesn’t tell you whether those genes are turned on or turned off.

This is where epigenetics comes in. Epigenetics is the science of modifications that alter gene expression. In simple terms, both DNA and the proteins that bind to DNA can be modified. This does not change the DNA sequence. But these modifications can determine whether a gene is active (turned on) or inactive (turned off).

This sounds simple enough, but here is where it really gets interesting. These modifications are affected by our diet, our lifestyle (BMI and exercise), our microbiome (gut bacteria), and our environment.

In today’s “Health Tips From The Professor” I am going to share a study (CQ Lai et al, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 112: 1200-1211, 2020) that looks at the effect of diet (low-fat versus low-carb diets) on a particular kind of DNA modification (methylation) that affects a gene (CPT) which influences our risk for metabolic diseases (obesity, high triglycerides, low HDL, insulin resistance, pre-diabetes, and type 2 diabetes).

[Note: For simplicity I will just refer to type 2 diabetes in the rest of this article. Just be aware that whatever I say about type 2 diabetes applies to other metabolic diseases as well.]

Previous studies have shown that:

- Methylation of the CPT gene is the only epigenetic change in the entire genome that is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes.

- CPT gene activity regulates multiple metabolic pathways that influence the risk of type 2 diabetes.

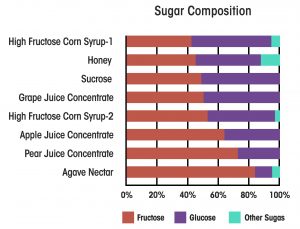

- High fructose and sucrose consumption increases CPT gene methylation in rats, and high fat diets suppress that methylation.

Based on those data, the authors hypothesized that carbohydrate and fat intake affect the methylation of CPT gene, which:

- Alters the activity of the CPT gene and…

- Affects the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Since we are talking about our diet making alterations to our DNA, we could consider this as an example of, “We are what we eat”.

Biochemistry 101: Why Is Nutrition So Confusing?

Now it is time for my favorite topic, Biochemistry 101. Along the way you will discover why nutrition is so complicated – and so confusing.

Now it is time for my favorite topic, Biochemistry 101. Along the way you will discover why nutrition is so complicated – and so confusing.

The CPT gene codes for a protein called carnitine palmitoyltransferase or CPT. CPT transports fats into the mitochondria where they can be oxidized to generate energy. Simply put, without CPT we would be unable to utilize most of the fats we eat. And, as you might expect, CPT is not required for carbohydrate metabolism.

- In a simple world where our DNA sequence determines our destiny, we would either have an active CPT gene or an inactive mutant version of the gene. If we had the mutant version of the CPT gene, we would be unable to use fat as an energy source.

However, we don’t live in a simple world. Epigenetic modifications alter the activity of the CPT gene. When the CPT gene is unmethylated it is fully active. Methylation inactivates the gene.

- In a simple world, a high fat diet would activate the CPT gene so our body would be able to utilize the fat in our diet. It would do that by decreasing methylation of the gene. Conversely, a high carbohydrate, low fat diet would decrease CPT gene activity by increasing methylation of the gene.

This is the one simple prediction that works exactly as expected.

- In a simple world, CPT would be involved in transport of fat into our mitochondria and nothing else. In that world, the activity of the CPT gene would only affect fat metabolism.

However, we don’t live in a simple world. By mechanisms that are not completely understood, carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT) also influences both insulin resistance and release of insulin by our pancreas. That means the activity of the CPT gene also affects our risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

- In the simplest terms, we can think of diabetes as an inability to properly regulate blood sugar levels. In a simple world, that would mean that carbohydrates are the problem, and we could reduce our risk of developing diabetes by restricting our intake of carbohydrates.

However, we don’t live in a simple world. There are short-term studies supporting the effectiveness of both low carb and low fat diets at helping to control blood sugar levels. However, longer term studies generally show that only whole food, low fat diets are associated with reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

In other words, healthy carbohydrates aren’t the problem. They are the solution for reducing your risk of type 2 diabetes. This isn’t intuitive. It isn’t simple. But the weight of evidence points in this direction.

[I should add the emphasis is on “healthy” carbohydrates. I am talking about diets that emphasize whole food sources of carbohydrates (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes), not diets loaded with sugar, refined carbohydrates, and highly processed foods.]

Confused yet? Don’t worry. The authors of this study combined all this information into a single, unifying hypothesis.

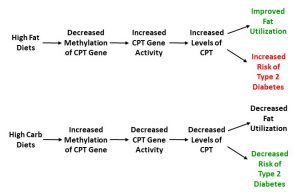

They proposed that the fat and carbohydrate content of the diet influence methylation of the CPT gene, which influences the activity of the CPT gene, which influences both fat metabolism and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Specifically, they proposed that:

- High fat diets reduce methylation of the CPT gene. This activates the CPT gene which results in more carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT) being produced. This improves fat metabolism, but also increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

- High carbohydrate, low fat diets increase methylation of the CPT gene. This inactivates the CPT gene which results in less CPT being produced. This is OK because there is little fat to be metabolized. However, it also has the advantage of reducing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

This can be visually represented as:

How Was This Study Done?

This study combined the results from 3,954 selected participants in three previous clinical trials:

This study combined the results from 3,954 selected participants in three previous clinical trials:

- The Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study.

- The Framingham Heart Study.

- The REGICORE study. This study is similar in design to the Framingham Heart Study except the participants were drawn from a region of Spain.

The participants were selected based on 4 criteria:

- The study they were in measured metabolic disease outcome.

- The study they were in included a detailed diet analysis.

- A DNA methylation analysis was performed on blood taken from these participants so that the methylation status of the CPT gene could be determined.

- mRNA levels were measured for the CPT gene (This is a measure of how active the gene is. Active genes will produce lots of mRNA. Inactive genes will produce very little mRNA).

The study then analyzed the data and looked at the associations between carbohydrate and fat intake with:

- Methylation of the CPT gene.

- Activity of the CPT gene (measured as the amount of CPT mRNA produced by the gene).

- Type 2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases.

Do Low Fat Diets Reduce The Risk Of Diabetes?

The authors systematically tested the predictions of their unifying hypothesis (To help you understand the significance of their findings, I am repeating the visual representation of their unifying hypothesis below):

- Methylation of the CPT gene was negatively associated with type 2 diabetes. Simply put, when the methylation of the of the CPT gene was high, the risk of type 2 diabetes was low. This confirmed the results of previous studies.

2) Carbohydrate and fat intake influenced methylation of the CPT gene. Specifically:

-

- Carbohydrate intake and the ratio of carbohydrate to fat intake were positively associated with CPT methylation. Simply put, a high carbohydrate, low fat diet resulted in increased methylation of the CPT gene.

-

- Fat intake was negatively associated with CPT methylation. Simply put, a high fat, low carbohydrate diet resulted in decreased methylation of the CPT gene.

3) Carbohydrate and fat intake influenced the activity of the CPT gene. Specifically:

-

- Carbohydrate intake and the ratio of carbohydrate to fat intake was negatively associated with CPT mRNA levels (a measure of CPT gene activity). Simply put, a high carbohydrate, low fat diet resulted in lower CPT gene activity. This means the CPT gene produced less CPT. And, combined with the previous data, it also means that methylation of the CPT gene decreases its activity.

-

- Fat intake was positively associated with CPT mRNA levels. Simply put, a high fat, low carbohydrate diet resulted in greater CPT gene activity. This means the CPT gene produces more CPT. And, combined with the previous data, it also means that reducing methylation of the CPT gene increases its activity.

4) CPT gene activity influenced the prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Specifically:

-

- High CPT gene activity was positively associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes.

-

- Low CPT gene activity was negatively associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Putting this all together, as the authors had predicted,

- High fat, low carbohydrate diets reduce methylation of the CPT gene. This activates the CPT gene which results in more CPT being produced. This improves fat metabolism, but also increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

2) High carbohydrate, low fat diets increase methylation of the CPT gene. This results in less CPT being produced. This is OK because there is little fat to be metabolized. However, it also has the advantage of reducing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

In short, the results of the study confirmed all the predictions of the author’s unifying hypothesis.

Putting it all together, the authors concluded, “Our results suggest that the proportion of total energy supplied by carbohydrate and fat can have a causal effect on metabolic diseases [like type 2 diabetes] via the epigenetic status (DNA methylation) of the CPT gene.” Simply put, their data suggested that high carbohydrate, low fat diets reduced the risk developing type 2 diabetes.

What Does This Study Mean For You?

Let me start by saying that occasionally I like to give you a peak behind the curtain and talk about emerging areas of research. We should think of this article as the beginning of an exciting new area of research rather than as a definitive study.

Let me start by saying that occasionally I like to give you a peak behind the curtain and talk about emerging areas of research. We should think of this article as the beginning of an exciting new area of research rather than as a definitive study.

I should start with the disclaimer that this study looks at associations between diet, methylation of the CPT gene, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Associations do not prove cause and effect. This study does not prove that epigenetic changes to the CPT gene caused the reduction in type 2 diabetes risk.

High carbohydrate and high fat diets likely influence the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in other ways as well. For example, the fiber in healthy high carbohydrate diets may support friendly gut bacteria that reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

I also don’t view this study as one that settles the debate as to whether low carb or low fat diets are better for reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes. It does not clinch the argument for low fat diets. Rather, this study suggests a mechanism by which low fat diets may reduce the risk of metabolic diseases.

In summary, this study does not end the debate as to whether low carb or low fat diets are best. However, it does remind us just how complex the human body is. It reminds us that simple assumptions about how foods affect our bodies may not be the correct assumptions. It also helps us understand why nutrition can be so confusing.

The Bottom Line

In recent years, DNA sequencing has become all the rage. It seems like everyone is offering to sequence your genome and tell you what kind of diet is best for you.

The problem is that DNA sequencing only tells you what genes you have. It doesn’t tell you whether those genes are active. Simply put, it doesn’t tell you whether those genes are turned on or off.

That is where epigenetics comes in. Epigenetics is the science of modifications that alter gene expression. In simple terms, both DNA and the proteins that bind to DNA can be modified. This does not change the DNA sequence. But these modifications can determine whether a gene is active (turned on) or inactive (turned off).

Epigenetics makes nutrition more complicated, and more confusing. For example, diabetes is characterized an inability to control blood sugar levels properly. Accordingly, it seems only logical that carbohydrates, especially sugars and simple carbohydrates, are the problem.

This study showed that high carbohydrate, low fat diets cause epigenetic modifications to a gene that reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases. Conversely, high fat, low carb diets have the opposite effect.

This mechanism is consistent with multiple long-term studies showing that whole food, low fat diets reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

This study does not end the debate as to whether low carb or low fat diets are best. However, it does remind us just how complex the human body is. It reminds us that simple assumptions about how foods affect our bodies may not be the correct assumptions. It also helps us understand why nutrition can be so confusing.

For more details read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.