What Does This Study Mean For You?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

There is a well-known health disparity in clinical studies related to health. For years most of the studies have been done by men for men. Women have been assumed to experience the same benefits and risks from diet choices as men. But that hasn’t always proven to be true.

There is a well-known health disparity in clinical studies related to health. For years most of the studies have been done by men for men. Women have been assumed to experience the same benefits and risks from diet choices as men. But that hasn’t always proven to be true.

The Mediterranean diet is no exception. For example, it has garnered a reputation of reducing heart disease risk for both men and women.

However, most studies on the Mediterranean diet have included primarily male participants or did not report sex specific differences in outcomes.

And the few studies that reported sex specific outcomes have been inconsistent.

- Some studies have found that men and women benefitted equally from the Mediterranean diet.

- Other studies have reported that men benefitted more than women.

However, these were all small studies. No meta-analyses have been reported that focused on the heart benefits of the Mediterranean diet for women.

The study (A Pant et al., Heart; 109: 1208-1215, 2023) I will describe today was designed to fill that gap.

How Was The Study Done?

The investigators started by screening the literature to find studies that:

The investigators started by screening the literature to find studies that:

- Measured adherence to the Mediterranean diet using the original MDS (Mediterranean Diet Score) or more recent modifications of the MDS.

- Included women ≥18 years without previous diagnosis of clinical or subclinical heart disease.

- Performed the study with only women participants or organized their data so that the data pertaining to women could be extracted from the study.

The investigators then performed a meta-analysis on data from 722,495 women in 16 studies published between 2006 and 2021 that met these criteria. These studies followed the women for an average of 12.5 years. The studies were primarily conducted in the United States and Europe.

The individual studies divided participants into either quintiles or quartiles and compared participants with the highest adherence to the Mediterranean diet to those with the lowest adherence.

- The primary outcomes measured were total mortality and the incidence of CVD, cardiovascular disease (defined as including CHD (coronary heart disease), myocardial infarction (heart attack), stroke, heart failure, and cardiovascular death).

- The secondary outcomes measured were stroke and CHD, coronary heart disease (heart disease caused by atherosclerotic plaque build up in the coronary arteries).

Is The Mediterranean Diet Healthy For Women?

When comparing the highest to the lowest adherence to the Mediterranean diet:

When comparing the highest to the lowest adherence to the Mediterranean diet:

- The incidence of CVD (cardiovascular disease) was reduced by 24%.

- Total mortality during the ~12.5-year follow-up was reduced by 23%.

- The incidence of CHD (coronary heart disease) was reduced by 25%.

- The risk of stroke was reduced by 13%, but that risk reduction was not statistically significant.

-

- The risk reduction for both CVD and total mortality was similar to that previously reported for men.

-

- Risk reduction for CVD was slightly higher for women of European descent (24%) than for women of non-European descent (21%). The later category included women of Asian, Native-Hawaiian, and African – American descent.

The authors concluded, “This study supports a beneficial effect of the Mediterranean diet on the primary prevention of CVD and death in women and is an important step in enabling sex-specific guidelines.”

I would add that the data from women of non-European decent suggests that genetic background and/or ethnicity may influence the effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet at reducing heart disease risk, but this effect appears to be small.

What Does This Mean For You?

The results of this study are not unexpected. But that doesn’t mean that studies with women are not valuable. There have been several examples in recent years where health or medical advice based on studies with men needed to be modified for females once the studies were repeated with women.

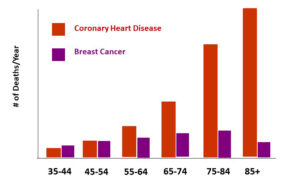

Before covering what this study means for you, I should point out that while women often fear breast cancer most, heart disease is their number one killer, as the graph on the left shows. In fact, a woman’s risk of dying from coronary heart disease is 6 times greater than her risk of dying from breast cancer.

Before covering what this study means for you, I should point out that while women often fear breast cancer most, heart disease is their number one killer, as the graph on the left shows. In fact, a woman’s risk of dying from coronary heart disease is 6 times greater than her risk of dying from breast cancer.

This study shows that following a Mediterranean–style diet lowers their risk of developing and dying from heart disease. But the Mediterranean diet is not alone in providing these health benefits. It is simply a whole food, primarily plant-based diet that reflects the food preferences of the Mediterranean region.

The DASH diet, which reflects the food preferences of Americans, and the Nordic diet, which reflects the food preferences of the Scandinavian countries, are equally heart healthy. In fact, any whole food, primarily plant-based diet will reduce the risk of heart disease. You should choose the one that best fits your food preferences and lifestyle.

Of course, diet is just part of a holistic approach for reducing heart disease risk. Other important risk reduction strategies include:

- Don’t smoke.

- Exercise and maintain a healthy weight.

- Manage stress.

- Avoid or limit alcohol.

- Know your numbers (cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood pressure, for example).

- Manage other health conditions that increase the risk of heart disease (high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol, for example).

The Bottom Line

Most studies on the heart health benefits of the Mediterranean diet have been done with men or have not analyzed the data from men and women separately. A recent meta-analysis combining data from 16 studies with 722,495 women showed that the Mediterranean diet was just as heart healthy for women as it was for men.

The authors concluded, “This study supports a beneficial effect of the Mediterranean diet on the primary prevention of CVD and death in women and is an important step in enabling sex-specific guidelines.”

For more details on this study and information on other diets that are heart healthy, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

_____________________________________________________________________________My My posts and “Health Tips From the Professor” articles carefully avoid claims about any brand of supplement or manufacturer of supplements. However, I am often asked by representatives of supplement companies if they can share them with their customers.

My answer is, “Yes, as long as you share only the article without any additions or alterations. In particular, you should avoid adding any mention of your company or your company’s products. If you were to do that, you could be making what the FTC and FDA consider a “misleading health claim” that could result in legal action against you and the company you represent.

For more detail about FTC regulations for health claims, see this link.

https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/health-products-compliance-guidance

_____________________________________________________________________

About The Author

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years.

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years.

Dr. Chaney won numerous teaching awards at UNC, including the Academy of Educators “Excellence in Teaching Lifetime Achievement Award”.

Dr Chaney also ran an active cancer research program at UNC and published over 100 scientific articles and reviews in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition, he authored two chapters on nutrition in one of the leading biochemistry text books for medical students.

Since retiring from the University of North Carolina, he has been writing a weekly health blog called “Health Tips From the Professor”. He has also written two best-selling books, “Slaying the Food Myths” and “Slaying the Supplement Myths”. And most recently he has created an online lifestyle change course, “Create Your Personal Health Zone”. For more information visit https://chaneyhealth.com.

For the past 45 years Dr. Chaney and his wife Suzanne have been helping people improve their health holistically through a combination of good diet, exercise, weight control and appropriate supplementation.