When Is Supplementation Important?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

Whole food, vegan diets are incredibly healthy.

Whole food, vegan diets are incredibly healthy.

- They have a low caloric density, which can help you maintain a healthy weight.

- They are anti-inflammatory, which can help prevent all the “itis” diseases.

- They are associated with reduced risk of diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers.

- Plus a recent study has shown that vegans age 60 and older require 58% fewer medications than people consuming non-vegetarian diets.

But vegan diets are incomplete, and as I have said previously, “We have 5 food groups for a reason”. Vegan diets tend to be low in several important nutrients, but for the purposes of this article I will focus on calcium and vitamin D. Vitamin D is a particular problem for vegans because mushrooms are the only plant food that naturally contain vitamin D, and the vitamin D found in mushrooms is in the less potent D2 form.

Calcium and vitamin D are essential for strong bones, so it is not surprising that vegans tend to have less dense bones than non-vegans. But are these differences significant? Are vegans more likely to have broken bones than non-vegans?

That is the question the current study (DL Thorpe et al, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 114: 488-495, 2021) was designed to answer. The study also asked whether supplementation with calcium and vitamin D was sufficient to reduce the risk of bone fracture in vegans.

How Was This Study Done?

The data for this study were obtained from the Adventist Health Study-2. This is a study of ~96,000 members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in North America who were recruited into the study between 2002 and 2007 and followed for up to 15 years.

The data for this study were obtained from the Adventist Health Study-2. This is a study of ~96,000 members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in North America who were recruited into the study between 2002 and 2007 and followed for up to 15 years.

Seventh-day Adventists are a good group for this kind of study because the Adventist church advocates a vegan diet consisting of legumes, whole grains, nuts, fruits, and vegetables. However, it allows personal choice, so a significant number of Adventists choose modifications of the vegan diet and 42% of them eat a nonvegetarian diet.

This diversity allows studies of the Adventist population to not only compare a vegan diet to a nonvegetarian diet, but also to compare it with the various forms of vegetarian diets.

This study was designed to determine whether vegans had a higher risk of hip fractures than non-vegan Adventists. It was performed with a sub-population of the original study group who were over 45 years old at the time of enrollment and who were white, non-Hispanic. The decision to focus on the white non-Hispanic group was made because this is the group with the highest risk of hip fractures after age 45.

At enrollment into the study all participants completed a comprehensive lifestyle questionnaire which included a detail food frequency questionnaire. Based on the food frequency questionnaire participants were divided into 5 dietary patterns.

- Vegans (consume only a plant-based diet).

- Lacto-ovo-vegetarian (include dairy and eggs in their diet).

- Pesco-vegetarians (include fish as well as dairy and eggs in their diet).

- Semi-vegetarians (include fish and some non-fish meat (primarily poultry) as well as dairy and eggs in their diet).

- Non-vegetarians (include all meats, dairy, and eggs in their diet). Their diet included 58% plant protein, which is much higher than the typical American diet, but much less than the 96% plant protein consumed by vegans.

Every two years the participants were mailed follow-up questionnaires that included the question, “Have you had any fractures (broken bones) of the wrist or hip after 2001? Include only those that came from a fall or minor accident.”

Can Vegans Have Strong Bones?

The results of this study were striking.

The results of this study were striking.

- When men and women were considered together there was an increasing risk of hip fracture with increasing plant-based diet patterns. But the differences were not statistically significant.

- However, the effect of diet pattern on the risk of hip fractures was strongly influenced by gender.

-

- For men there was no association between diet pattern and risk of hip fractures.

-

- For women there was an increased risk of hip fractures across the diet continuum from nonvegetarians to vegans, with vegan women having a 55% higher risk of hip fracture than nonvegetarian women.

- The increased risk of hip fractures in vegan women did not appear to be due to other lifestyle differences between vegan women and nonvegetarian women. For example:

-

- Vegan women were almost twice as likely to walk more than 5 miles/week than nonvegetarian women.

-

- Vegan women consumed more vitamin C and magnesium, which are also important for strong bones, than nonvegetarian women.

-

- Vegan women got the same amount of daily sun exposure as nonvegetarian women.

- The effect of diet pattern on the risk of hip fractures was also strongly influenced by supplementation with

calcium and vitamin D.

calcium and vitamin D.

-

- Vegan women who did not supplement with calcium and vitamin D had a 3-fold higher risk of hip fracture than nonvegetarian women who did not supplement.

-

- Vegan women who supplemented with calcium and vitamin D (660 mg/day of calcium and 13.5 mcg/day of vitamin D on average) had no increased risk of hip fracture compared to nonvegetarian women who supplemented with calcium and vitamin D.

- In interpreting this study there are a few things we should note.

-

- The authors attributed the lack of an effect of a vegan diet on hip fracture risk in men to anatomical and hormonal differences that result in higher bone density for males.

-

- In addition, because the average age of onset of osteoporosis is 15 years later for men than for women, this study may not have been adequately designed to measure the effect of a vegan diet on hip fracture in men. Ideally, the study should have enrolled participants who were at least 60 or older if it wished to detect an effect of diet on hip fractures in men.

-

- Finally, because the study enrolled only white, non-Hispanic women into the study, it does not tell us the effect of a vegan diet on women of other ethnicities. Once again, if there is an effect, it would likely occur at an older age than for white, non-Hispanic women.

The authors concluded, “Without combined supplementation of both vitamin D and calcium, female vegans are at high risk of hip fracture. However, with supplementation the excessive risk associated with vegans disappeared.”

Simply put, vegan diets are very healthy. They reduce the risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, some cancers, and inflammatory diseases.

However, the bad news is:

- Vegan women have a lower intake of both calcium and vitamin D than nonvegetarian women.

- Vegan women have lower bone density than nonvegetarian women.

- Vegan women have a higher risk of hip fracture than nonvegetarian women.

The good news is:

- Supplement with calcium and vitamin D eliminates the increased risk of hip fracture for vegan women compared to nonvegetarian women.

When Is Supplementation Important?

Much of the controversy about supplementation comes from a “one size fits all” mentality. Supplement proponents are constantly proclaiming that everyone needs nutrient “X”. And scientists are constantly proving that everyone doesn’t need nutrient “X”. No wonder you are confused.

Much of the controversy about supplementation comes from a “one size fits all” mentality. Supplement proponents are constantly proclaiming that everyone needs nutrient “X”. And scientists are constantly proving that everyone doesn’t need nutrient “X”. No wonder you are confused.

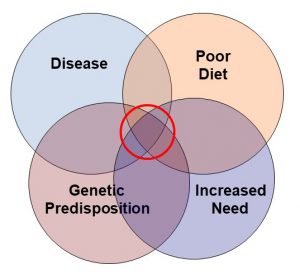

I believe in a more holistic approach for determining whether certain supplements are right for you. Dietary insufficiencies, increased need, genetic predisposition, and diseases all affect your need for supplementation, as illustrated in the diagram on your left. I have discussed this approach in more detail in a previous issue (https://www.chaneyhealth.com/healthtips/do-you-need-supplements/) of “Health Tips From the Professor”.

But today I will just focus on dietary insufficiencies.

- Most Americans consume too much highly processed fast and convenience foods. According to the USDA, we are often getting inadequate amounts of calcium, magnesium, and vitamins A, D, E and C. Iron is also considered a nutrient of concern for young children and pregnant women.

- According to a recent study, regular use of a multivitamin is sufficient to eliminate most these deficiencies except for calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D. A well-designed calcium, magnesium and vitamin D supplement may be needed to eliminate those deficiencies.

- In addition, intake of omega-3 fatty acids from foods appears to be inadequate in this country. Recent studies have found that American’s blood levels of omega-3s are among the lowest in the world and only half of the recommended level for reducing the risk of heart disease. Therefore, omega-3 supplementation is often a good idea.

Ironically, “healthy” diets are not much better when it comes to dietary insufficiencies. That is because many of these diets eliminate one or more food groups. And, as I have said previously, we have 5 food groups for a reason.

Take the vegan diet, for example:

- There is excellent evidence that whole food, vegan diets reduce the risk of heart disease, diabetes, inflammatory diseases, and some cancers. It qualifies as an incredibly healthy diet.

- However, vegan diets exclude dairy and meats. They are often low in protein, vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, iron, zinc, and long chain omega-3 fatty acids. Supplementation with these nutrients is a good idea for people following a vegan diet.

- The study described above goes one step further. It shows that supplementation with calcium and vitamin D may be essential for reducing the risk of hip fractures in vegan women.

There are other popular diets like Paleo and keto which claim to be healthy even though there are no long-term studies to back up that claim.

- However, those diets are also incomplete. They exclude fruits, some vegetables, grains, and most plant protein sources.

- A recent study reported that the Paleo diet increased the risk of calcium, magnesium, iodine, thiamin, riboflavin, folate, and vitamin D deficiency. The keto diet is even more restrictive and is likely to create additional deficiencies.

- And it is not just nutrient deficiencies that are of concern when you eliminate plant food groups. Plants also provide a variety of phytonutrients that are important for optimal health and fiber that supports the growth of beneficial gut bacteria.

In short, the typical American diet has nutrient insufficiencies. “Healthy” diets that eliminate food groups also create nutrient insufficiencies. Supplementation can fill those gaps.

The Bottom Line

Vegan diets are incredibly healthy, but:

- They eliminate two food groups – dairy, and meat protein.

- They have lower calcium and vitamin D intake than nonvegetarians.

- They also have lower bone density than nonvegetarians.

The study described in this article was designed to determine whether vegans also had a higher risk of bone fractures. It found:

- Vegan women who don’t supplement have a 3-fold higher risk of hip fracture than nonvegetarian women.

- The increased risk of hip fractures in vegan women did not appear to be due to other lifestyle differences between vegan women and nonvegetarian women.

- Supplementation with calcium and vitamin D (660 mg/day of calcium and 13.5 mcg/day of vitamin D on average) eliminated the difference in risk of hip fracture between vegan women and nonvegetarian women.

In the article above I discuss the importance of supplementation in assuring diets are nutritionally complete.

- In short, the typical American diet has nutrient insufficiencies. “Healthy” diets that eliminate food groups also create nutrient insufficiencies. Supplementation can fill those gaps.

For more details about the study and a discussion of which supplements may be needed to assure nutritionally adequate diets, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.